Ten-Minute Methodology: When Index is a “Dirty Word”

-

Created on 10 November 2015

By Judy Kellar Fox, CG® Genealogical work supported by indexes alone can be unreliable. What? What’s wrong with the Social Security Death Index (SSDI)? It comes from a reliable source. Other indexes are good, too! Why not use them and cite them as sources?[1]

Genealogical work supported by indexes alone can be unreliable. What? What’s wrong with the Social Security Death Index (SSDI)? It comes from a reliable source. Other indexes are good, too! Why not use them and cite them as sources?[1]

Standard 38, Source Preference, gives us the answer: “Whenever possible, genealogists prefer to reason from original records that reliable scribes carefully created soon after the reported events.”[2]

Standard 13, Source-Based Content, points out that our research plans may include indexes. However, when it’s possible, we “follow such materials to original records and primary information.”[3]

What is an index, anyway? We usually use the word to refer to an alphabetical list or guide that points us to more information elsewhere. By nature it is a derivative source, something created from something else.

Other so-called indexes offer much more than direction to find an item. Some include extracted information, helping us distinguish people of the same or a similar name.

Here’s an example of information gleaned from two online indexes. It gives a pretty good overview of one man.

| SSDI[4] | California death index[5] | |

| Name | John Kellar | John M Kellar |

| Social Security Number | 560-03-9682 | 560-03-9682 |

| Death date | Aug 1964 | 20 Aug 1964 |

| Death place | Sonoma [County], California | |

| Birth date | 14 Jun 1879 | 14 Jun 1879 |

| Place where benefit was sent | California | |

| State (Year) SSN issued | California (Before 1951) | |

| Birth place | Pennsylvania | |

| Gender | Male | |

| Mother’s name | Philippi |

So what’s wrong with these indexes? Sure, they are derivative sources, but not all derivatives are bad. What can make index a “dirty word”?

There are two issues.

- Extracting information involves recopying it, which introduces the possibility of error, no matter how carefully the extracts are proofread.

- Creators of the indexes make choices about what information is extracted and what is left behind. Usually we are not given all the information from the record. This could lead to incorrect assumptions about what we do have. And what we’re missing could be clues to lead our research in productive directions.

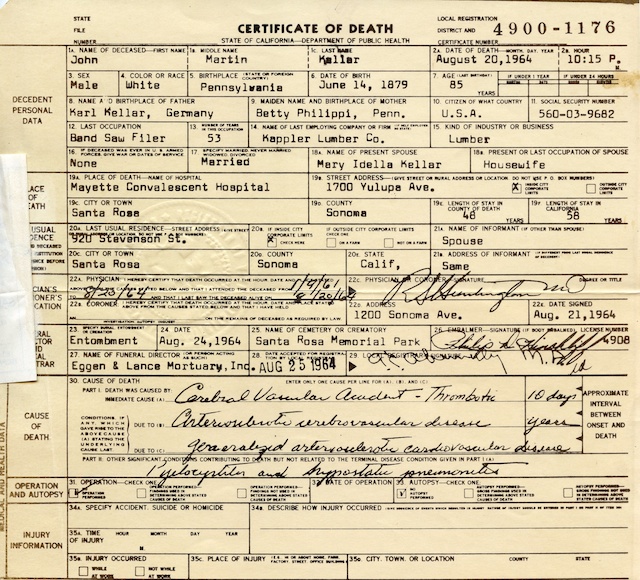

The original death certificate for the above example reveals the extraction choices made by the California death index.[6]

If research stopped at the index level, the following information would be missed:

- employment

- father’s name and birthplace

- mother’s given name and birthplace

- spouse’s name and that she was the informant for the personal information

- residence

- length of residence in the state and county

- medical and health data

- burial information

Much of this information is primary, provided by knowledgeable informants (the spouse, the physician, the embalmer). This is one reason we are not satisfied with index entries alone. The original source may have errors, but they are not errors of transcription that could creep in when making an extract.

Indexes are useful in pointing the way. We note the information they offer and then set off to find an original source for the information we need.

Here’s the rub. First, we have to figure out if it is even possible to get the originals an index points to. The next step is learning how to get the originals. In the case of many online records, a digitized image of an original document is available with a few more mouse clicks. Other times we must determine the repository and then make contact in person or via telephone, email, or snail mail. Sometimes we are hamstrung by legal restrictions on records access, as with some recent vital records.

In the case of our death certificate example, Sonoma County, California, death records are available on Family History Library microfilm through 1919 only.[7] For a more recent death we can apply to the county or to the California Department of Public Health. (Ancestry even provides a link.) Oh yes, and we have to pay $21 and send an application through the mail. Or we can order online through a third-party site, which reduces the wait and increases the fee.

So here’s the question: Our n-generation genealogy includes many people in recent generations for whom death certificates are available, but not published, not on microfilm, and not online. It’s an expensive and time-consuming proposition to order death certificates for all the individuals. Yet genealogy standards urge us to use original sources. If we don’t, if we opt to use the “dirty word,” our list of source citations can include many derivative indexes. What do we do?

Time and money. That’s often the cost of accessing original records. However they almost always give us far more than the index, and we can judge for ourselves the quality of the source and perhaps the reliability of the information in it. We don’t have to worry about introduced errors. We usually have new hints to work with, too. And we have the satisfaction of working to standards by getting closer to original records and primary information.

Watch for the next SpringBoard post for ways to meet standards when the original records indexes point to are lost, destroyed, or otherwise inaccessible.